Shorter days and darker nights doesn't mean fewer photo opportunities! We asked the Analogue Wonderland Instagram community to share their favourite films for shooting after dark - from tungsten-balanced colour to gritty black and white classics. Here are your top five picks for low-light photography.

Recent posts

Shop the article

Analogue Appeal: Why Do People (Still) Shoot Film?

By Paul McKay

The internet is full of personal manifestos about why people shoot film. I could certainly write one for myself - referencing the special joy of holding a 50-year old camera to capture beautiful images. But here at Analogue Wonderland we are uniquely placed to take a wider view of the question: every year we hear from thousands of film shooters about their persistent attachment to analogue technology in a digital world.

And the reality? There is no single answer! Instead we see a mishmash of complementary themes and motivations. So I have canvassed our community to pull out the key trends, themes and topics to provide a comprehensive overview of the eternal question: why do we still shoot film? This article even sparked a piece in the Guardian on Gen Z's relationship with film! Enjoy 👇🏼

Film vs digital?

Let's back up for a second and think about how we got to the question of why people shoot film. For the first century of photography, film was the only option for hobbyists and professionals alike. Then the technology of electronic image sensor chips hit a tipping point and in 1990 the launch of the 'Dycam Model 1' - the first consumer digital camera sold in the USA - heralded the start of a revolution in the photography market.

Throughout the 90s and 00s, while the resulting transition of film --> digital photography was in progress, there was a regular debate that played out in camera clubs and forums around the world: 'which is better, film or digital?' And at first it was easy. Digital cameras were low-resolution, expensive, and they had serious limitations on battery life and memory capacity. Admittedly an extreme case but the Dycam Model 1 took photos 376 pixels wide, had 1MB of internal memory and cost $1,000. That 1990 price is equivalent to ~$2,420 or £1,950 in today's money.

But as time passed and new models were released it became clear that digital's technical abilities were quickly overtaking film, and these days it's not even a contest. The Canon EOS 90D has a 32.5MP sensor, and an ISO range up to 25,600. The cost of SD memory has dropped to allow more than 300,000 images on a single card for under £20, and the iPhone has been advertising its capability as an effective pocket-sized camera since 2014.

When the balance first moved in the favour of digital the debate evolved (devolved?) into accepted wisdom that said digital was technically better for commercial work but film had an indefinable quality that you could just 'see'.

One of these was shot on an iPhone; the other on a 35mm film point-and-shoot. Can you identify which, and what gave it away?

Then Instagram arrived, exploding the popularity of digital post-photo effects - filters - which in turn lead to countless tutorials on YouTube and blogs of 'how to get the film look' using advanced Photoshop tools. Those tools became easier to use, packaged and sold with the promise of removing analogue photography's last unique benefit: the look of film.

And yet...here we are. Kodak has increased its production of 35mm film every year since 2015, Harman Technology invested in developing 'Phoenix' as the first colour film to ever be produced on their Ilford site, and Pentax are making promising noises about a brand new film camera. Tiktok accounts showing people loading film cameras - and the results they receive - reach millions of views, and the profession of 'analogue sports photographer' is a thing once again!

Hey Miles - the 1920s called and they want their camera back 😅

So what's going on?

After diving into the thousands of answers on our annual survey, gathering responses on our Instagram posts and speaking to hundreds of individuals I think we can safely say that there is a powerful set of forces at work. And these forces are not unique to photography - there is a wider digital backlash happening in society at the moment.

The revenge of analogue

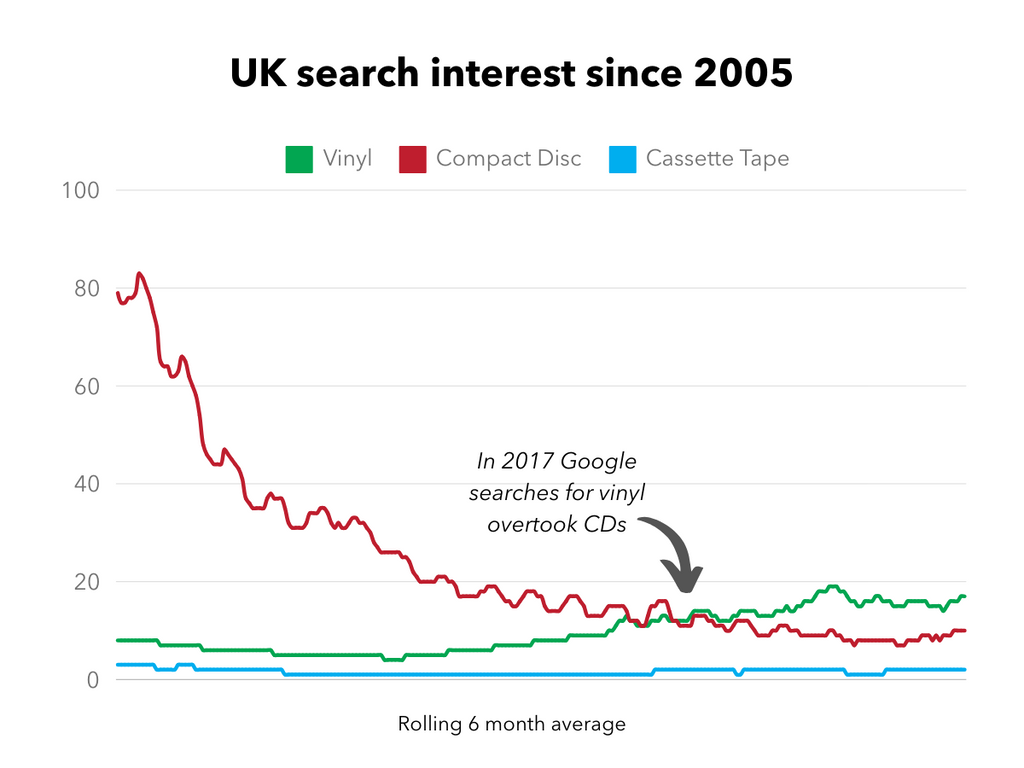

I remember reading a fantastic book called ‘Revenge of Analog’ that drew a comparison between film photography, vinyl, board games, hardback books and more to show that there was a consistent pattern for items that were meant to be made extinct by digital. PlayStations were supposed to kill board games, the Kindle was the death knell of physical books, and vinyl has survived cassettes, CDs, minidiscs, iTunes, and now Spotify!

The pattern was this: during the first days of a new technology there is a lot of publicity, advertising, and noise from the media. This drives mass adoption of the new way of doing things. The convenience, the lower cost, the apparent ‘democratisation’ of digital are (rightly) celebrated and the market expands. The share of the old technology drops from 100% to 50% to 10% very quickly…but then at some point before 0% it stabilises and starts to rise.

I highly recommend the book for anyone interested in the wider topic - the author David Sax researched several industries to give a fantastic tour of 'real things and why they matter’. But we can expand his chapter on film to take account of the new generation of photographers that have joined the analogue ranks since its publication in 2016 - and as recent world events have accelerated some of the trends even further.

If I had just 20 seconds to explain the most common reasons people give for shooting film then I'd say: "my photos look better", "it's a fun thing to do", "it slows me down" and "I love the supportive people I meet".

But even this is a little simplistic 🧐 So let's break it down and spend time on each of the core truths about why we shoot film:

- Aesthetic

- Creative Challenge

- Tactile (experience)

- Nostalgia

- Experimentation

- Anticipation

- Mindfulness

- Community

Download the full size graphic here

1. Aesthetic

The grain in the sky, the vignetting, the eye-catching colour palette... hang on. These are all entirely subjective 😂 And although most film people will happily wax lyrical about why they love the look of their photos, they will often be talking about different things!

Some folk love the high contrast of Kodak Tri-X; others the softer feel of Ilford HP5 Plus. Personally I can never get over the vivid colours of Kodak Ektar but to others it's over-saturated. Meanwhile the extreme blur at the edge of my Holga photos would be entirely avoidable if I used a better quality lens.

It's my look 🙌🏼

There is no single 'film' aesthetic - and lots of different film looks. To lob another fly into the ointment, any of these effects can be mimicked in Photoshop anyway.

So why does it keep coming up?

Actually it comes up because aesthetics are deeply personal preferences, and because film emulsions are wonderfully consistent. I've got to the stage where I can usually spot which film has been used whenever I see images flash up in customer reviews on our Wall of Inspiration. You also don't need to do anything with film to make it look like 'your photography' once it's been processed by a top film lab.

The roll will come back to you as negatives, scans or prints with an aesthetic that is always the same film-to-film. So if you love shooting high-contrast black and white film with plastic lenses and bright flash, and that's how you define your 'film aesthetic' then you can replicate it time and time again with just your camera. No screen needed - no fiddling with settings - no adjustments made 'in post'. Nothing else required to achieve your consistent creative vision.

Or as cinematographer Suzie Lavelle puts it "From a creative point-of-view, with film you can put your energies into the visual storytelling, rather than having to spend time on trying to make it look and feel like film when you shoot digitally." We occasionally compile lists like 'the best colour films' which show the vast difference you can get from different emulsions - this keeps things fun and exciting for all analogue shooters.

Suzie on the set of 'The End We Start From' - an upcoming thriller starring Jodie Comer and shot on Kodak 35mm film

2. Creative challenge

Shooting film is an exercise in choice. As soon as you’ve loaded a film into your camera then you’re locked into certain creative options. You spot a colourful bloom of different flowers and you have Ilford HP5 in your camera? Tough luck! Did you load a low-speed film for holiday (something like Kodak Pro Image perhaps) anticipating lots of sun, and then found yourself inside a beautiful old cathedral lit only by two candles at the door? Whoops! You’ve brought one roll of 120 film but are standing in a visual paradise with more than 12 photographic options? That’s going to hurt!

Digital photographers can flick a switch or press a button to change colour, ISO, and many more visual settings that affect how the sensor ‘sees’ the scene in front of the lens - and the idea of the gear limiting how many photographs you can take in a single day is laughable. But not with film. Surely this is a downside, right?

For most professional instances - absolutely. But for folks who are looking to stretch their creative muscles it’s not that simple. There is a well-known psychological phenomenon called ‘Choice Overload’. Put simply ‘when given more options to choose from, people tend to have a harder time deciding, are less satisfied with their choice, and are more likely to experience regret’.

Film works perfectly to counter choice overload by separating creative options into distinct buckets. Loading a film? This is when you choose the colour palette, choose the ISO, and the contrast, grain and other aesthetic options - all at once. But when you’ve closed the camera back that's done, it's fixed. So you have no choice but to think about composition - along with shutter and aperture settings if your camera allows. Disposable cameras are the extreme case here and it's one of the reason they're making a comeback of their own!

[Side note: this is also why I don’t like zoom lenses. They add a choice - focal length - back into the mix. With a prime lens you can't change that, your perspective is fixed. So to change the distance to your subject you have to move your feet or height instead, once again grounding you in your physical space.]

If a digital camera has 5 colour settings, 5 contrast settings, and 20 ISO options then that combines to offer 500 different ‘looks’ for a single photograph 🤯 And even if you try to pretend they don’t exist, there’s compelling scientific evidence to show the act of ignoring choices still causes strain on your mental (creative) resources. So release that strain! Take away those options and invest the time into thinking what might look good instead. Move your feet - wait for time to bring things in and out of shot - observe how the light moves around the scene - and capture a moment that matters.

Get close. And possibly underwater...

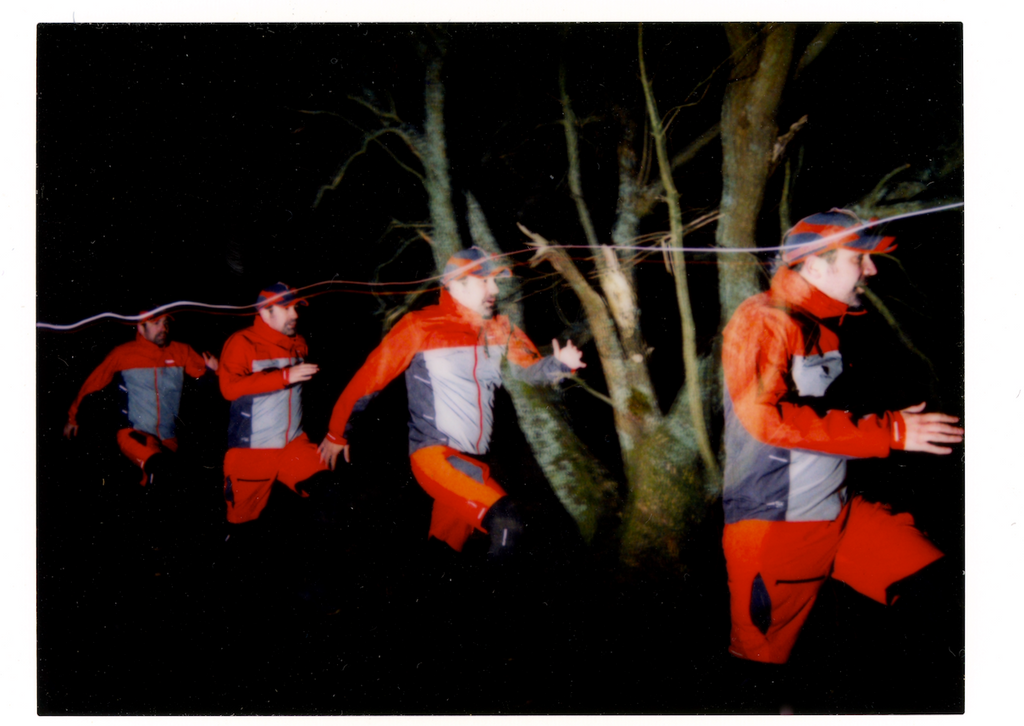

It can also force you to adapt or create new ways of solving technical issues. For example my friend Luke wanted a new standout photo for his running profile, and we came up with the idea of a combined multi-exposure and light trail image shot on Instax Mini. Great! But… my Instax camera doesn’t have a multiple exposure setting. And for light trails you need darkness but the flash is too weak to make any difference at distance. Hm.

So we ended up jamming the shutter open - “bulb mode” 😂 - and asking another friend to stand to one side with a handheld remote flash, firing it a few times while Luke ran towards the camera. We had to wait until 10pm for the sun to completely set and it took an hour and a half of trial-and-error to get right but my goodness the satisfaction at the end was real.

Lomography are a huge advocate for this approach to photography - and have published a set of ‘Golden Rules’ to help people think about the mindset of capturing images, rather than being distracted by what gear or settings they’re using. And if this doesn't resonate, you'd rather be more accurate with your exposures, then you might be more like Donald from KEKS!

3. Tactile experience

Tactile relates to our sense of touch, and with analogue photography this encompasses the physical and tangible nature of the craft. As soon as you pick up an unfamiliar film camera you’ll be assessing its weight, its shape, its feel in your hands. You’ll then start to look for the shutter, whether it has an ISO ring or shutter settings, is the lens detachable or fixed - and all of these features are likely to be physical mechanical parts of the camera. You might then load the camera, sliding the lever or pushing the button to open the back. Feeding the film onto the take-up spool and testing the tension before closing it up and getting ready to shoot.

A good camera just feels right - as modelled by Edwin

There is a ritual and a routine that connects your senses with your body with your camera - and one that you will never get from pressing a specific point on a smartphone screen to open the camera app.

It’s not just our sense of touch that is brought into play by film photography. I love the smell of a freshly opened canister of film! I have friends who can identify camera models by the sound of the shutter opening and closing. And this multi-sensory experience grounds us in our physical reality and makes it easier to see - and capture - the world around us.

The experience doesn't end with the moment of image capture either. Anyone who has developed their own film will know that you get a tangible feel for the process. You have to remember temperatures, time, and other physical measures. It's a bit like baking a cake - although with film you really must not lick the icing 😂 - and the first moment that you lift the negative strip and see your photos appear is one of true magic.

I helped teach a home-developing workshop at the 2023 Analogue Spotlight in Nottingham, and captured the exact moment that people saw the results for the first time. Consistent big grins 😁

I also want to mention how film photography is tangible - another word about the physicality of analogue - but often used specifically within the community in relation to film's opposite nature from AI and digital files. When you take a film photograph the frame exists in the real world. It is an object that can be viewed in different ways (projected, printed or scanned) but ultimately sits as an unique combination of chemicals and materials that can be picked up and handles.

This makes it verifiable in the same way as an artefact from an archeological dig - you can date it, review it versus the other negatives from the images on the negative, and even destroy it permanently. You can't duplicate or replicate the physical photograph.

4. Nostalgia

There are two elements to nostalgia in film photography. The first is the simple ‘direct’ nostalgia. Folks who used to shoot film back before digital, rediscovering their gear or the brands they used to love, and finding that their muscle memory for loading film or preparing a developing reel is still there. I’ve watched countless people walk up to our stand at the Photography Show or come into our lab and begin by saying something along the lines of “haha I can’t believe this is still a thing!” And within five minutes they’ll be telling me that they loved learning film photography at school or college, how they used to have a darkroom in their shed, their favourite cameras over the years, the photos that they took and where they displayed them. And then the conversation moves on: “Actually I probably still have the Canon AE1 in my cupboard upstairs” and finally: “Go on then, I’ll grab a couple of rolls of Ilford and we’ll see if it still works”

There is a deep joy in remembering pleasures from years before - and then realising that there is a vibrant, welcoming community that is carrying the torch for the next wave of photographers to experience those same pleasures. If film photography doesn’t spark that particular feeling for you then - depending on your own youthful pastimes - how do you feel about the recent resurgence of Pokemon? Scalextric? Tony Hawk video games? 80s clothes? Tamigotchis?

Does seeing the old Canon branding make your heart skip a beat? ❣️

Secondly - and personally I find this more interesting - I’ve seen a generational nostalgia that younger photographers experience. These are people who grew up in the 21st century and have no direct memories of analogue ‘the first time round’ but have hand-me-down cameras, equipment, and photo albums from family and friends to create a rich sense of connection. For example in my own camera collection I have an Olympus OM-1 camera from my father-in-law, a Canon AE1 kit from my uncle, and an Ilford Sportsmaster from my grandparents that has my dad’s first childhood address written on the case: ‘if found please return to’.

When I use these cameras I love the feeling that I’m holding a piece of family history. They have been capturing holidays and important moments in the lives of my relatives over several decades - in some cases they’re now taking photos of their third generation of McKay! Somehow I doubt that my grandkids will ever take my iPhone 12 out for a photowalk, or that my Canon DSLR from 2009 will survive half a century of regular use.

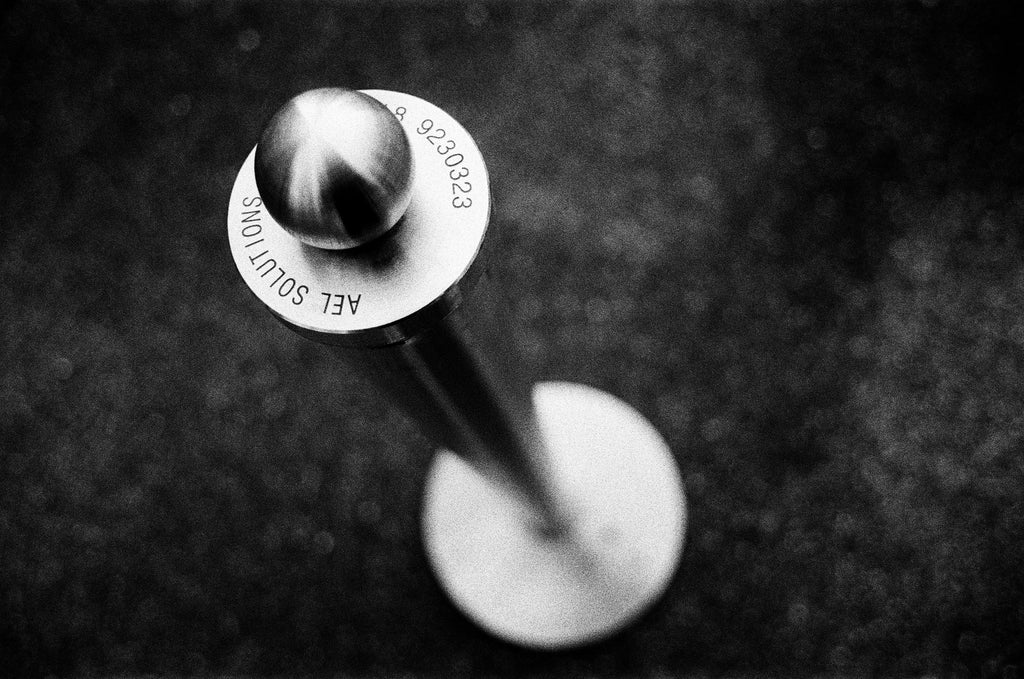

"I took this photo a couple of months ago on Kodak Tri-X 35mm film with my Olympus OM-1" is a sentence that you could have said at any time in history since 1972. And in this case it's true: a street pole shot in Oxford on a community photowalk

It’s not just the cameras that speak to the past. The Kodak Tri-X emulsion is over 60 years old and was used in countless iconic images across the mid-late 20th Century. Ferrania has been making film in Italy since the 1920s, and Kodak Vision film is the canvas on which Hollywood movies have delighted audiences throughout the golden age of cinema. This gives a beautiful and authentic sense of history while you’re using the same chemistries, the same films and the same cameras to capture you own modern photographs.

5. Experimentation

Linked to the creative constraints, but taking the concept even further: film photography allows you to play with a huge variety of visual tricks and techniques simply by existing in a physical form. Before, during, and after you've taken the photo.

Starting with 'Before' techniques, you may have seen YouTube videos of film souping where rolls of film are left in liquid (wine, seawater, coffee) to add an unpredictable streak to images later. If you don’t have the time or confidence to plan this yourself, brands like revolog provide 35mm films with effects already applied. They are random and vary from frame-to-frame - a very different proposition to deliberate digital filters. You have to pray to the film gods and be comfortable with serendipity.

What a photo! Shot on revolog Tesla 1 35mm film

While you are shooting the film there are different tricks to manipulate the way light is captured. One of my favourites is using red/orange/yellow filters - matched with panchromatic black and white film - to impact the strength at which different parts of the light spectrum are registered in the image. It makes a significant difference to the look and feel of the photo, and you can deliberately dial up and down contrast and detail as a result.

The roll of film itself remains a tangible part of the process, which you can play with in different ways. You can partner with other film photographers to create double-exposure projects, taking turns to take photos on the same roll of film. You can create a physical comic strip with your negatives by shooting a deliberate sequence of images with a choreographed scene and movement between frames.

I've combined the 'on film' effect of Lomochrome Turquoise with the 'in camera' technique of double exposures to create a multi-layer photo of the forest

And finally we have analogue techniques for after the film is exposed. Emulsion lifts is a popular method of manipulating Polaroid pictures - releasing them from the constraints of their original frame and transposing them to other surfaces. Cross-processing is an umbrella term for using the ‘wrong’ chemistry with films to get a slightly different final look. The most common version is putting E6 slide film through C41 chemistry, but there are lots of variations on the theme.

I've also seen mixed media projects that incorporate prints, scans and negatives - all from a single roll of film. This allows the artist to explore a concept much more comprehensively than is possible with images alone.

6. Anticipation

There is a delicate balance between anticipation and impatience. Film photography sits happily in the middle: you cannot immediately see the results, but the timescale isn’t unbearable. Polaroid and Instax film develops in minutes, many labs offer an express turnaround service to develop in under an hour, and mail order labs should provide scans within a week or two from posting.

Waiting for scans like...

This provides you with a ‘Christmas morning’ effect: you get the build up and the nerves of finding out whether your carefully planned photography has paid off. Did your camera work as expected? Did the experiments behave? Was the film the right choice for the shoot? And whether the answer is ‘yes’ or 'no' to those questions, the dopamine hit when it comes is all the greater for the wait!

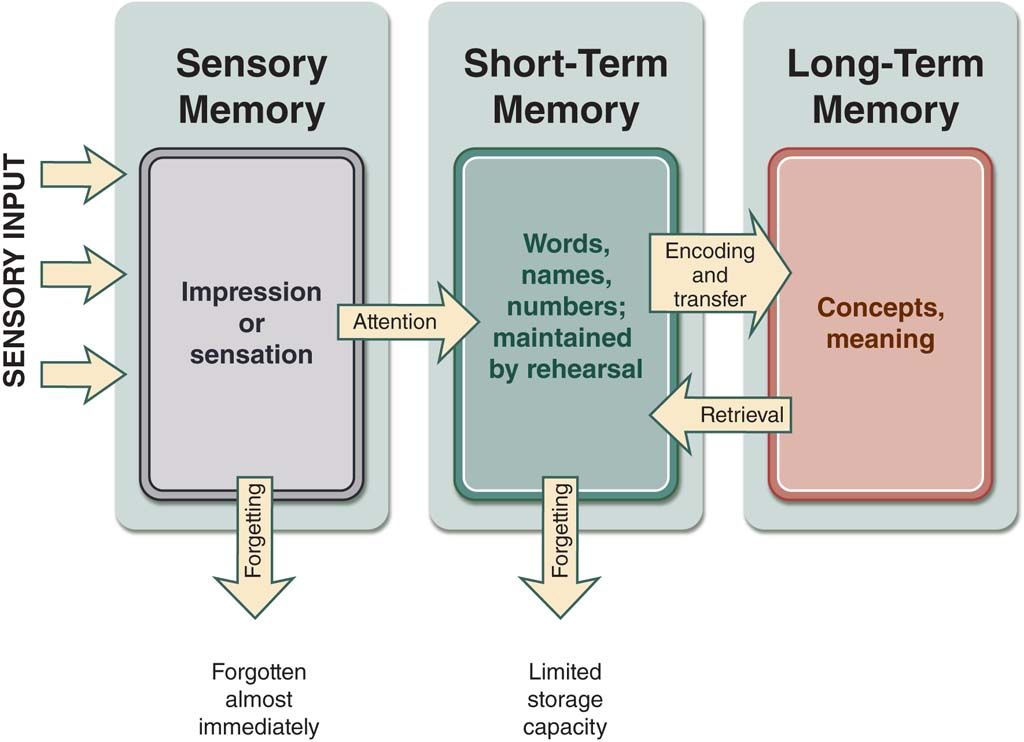

The anticipation also allows you to see the results of your photography with the aid of a neat physiological benefit to do with recall. You may know that brains process memories in different ways depending on their recency. If you take a photo on your digital camera and look at it within a few seconds or minutes you are operating with short-term memory. This means that you are reacting to the current environment and seeing the result in the context of what’s in front of you. You are likely to focus on details and accuracy and technical aspects of the photo.

Credit GetGoally.com

In contrast when you are forced to wait a couple of days (at least!) to see your analogue photos then you will be viewing the images with the benefit of your long-term memory. Your brain will incorporate emotions, weave in social context, and reference our mammalian reward centre to provide a more complete experience of viewing the photo. You will be judging it within the framework of how you feel - in retrospect - about the day and moment you captured. You can still zoom in on the technical details and cooly analyse the composition, but you will also have a strong emotional attachment to the photograph.

And generally speaking if (a) the technical analysis holds up and (b) your emotion matches the mood that you were trying to capture - then that’s likely to be an award-worthy photograph!

7. Mindfulness

”Mindfulness is the basic human ability to be fully present, aware of where we are and what we’re doing, and not overly reactive or overwhelmed by what’s going on around us.” - Mindful.org. There is a strong body of evidence to show that being mindful in this way has an enduring positive effect on our mental health. Put simply: being able to stay in the ‘now’ rather than the past or the future is the most peaceful state for our minds to occupy.

On holiday and not a screen in sight. But I was still taking photos!

Mindfulness as a concept has exploded in recent years thanks to the negative impact that technology has on our ability to stay mindful and present. We carry devices everywhere we go that interrupt us. Emails about meetings in the future, notifications on work that we did last week, Instagram posts that compare a utopian ideal unfavourably with our own lives, and so much more. This continually interrupts our train of thought and takes us out of the 'now'.

Film photography allows us to escape that pressure, at least for a time. Your 35mm film camera is not about to buzz with a phonecall or WhatsApp notification 🤐👍🏼

Funnily enough there is a Bluey episode literally about this idea: that it's easier to capture meaningful moments if you leave your smart devices behind

You can be engaged with your environment, connect with others who have joined your photowalk or studio shoot, and remain absorbed in the physical world. It helps that we often shoot film at beautiful locations, or on epic holidays, or at weddings or festivals that encourage us to explore the ‘now’, but even leaving your phone at home and picking up a camera to walk ten minutes from your home will give you a rest from the digital grind.

This plays heavily into the ‘Tactile’ topic we discussed earlier: mindfulness experts will often talk about grounding yourself in your physical surroundings, and that's much easier when you’re doing something that is intrinsically analogue and solid. It's also heavily linked with the idea that film 'slows you down' - you have the opportunity, time and mental headspace to pause before composing your image and pressing the shutter.

To be clear: analogue shooters aren’t luddites or anti-digital. The connectivity of the internet has allowed for new connections and strong relationships to develop around the world, with folks sharing tips and inspiration to help each other create and enjoy film photography. The learning resources on YouTube and TikTok are fantastically helpful, especially for those who learn visually instead of by text.

I have multiple film photography friends that I have only ‘met’ on Instagram. We’re also in the middle of building a Discord server to help pull together communication strands and community conversations from various channels into one simple place - and there are some fantastic digital cameras that avoid the 'screen and connection' trap.

Ilford run one of my favourite YouTube channels with a wonderful mix of inspiration and educational content

But there is a big difference between choicefully investing in digital communication for the purpose of - for example - teaching yourself a specific technique or gathering inspiring examples of a photography genre, versus being sucked into everyone else’s expectations of what you ‘should’ be doing.

The latter takes you away from mindfulness, and boots you out of your mindset of free-flowing creativity. Analogue photography’s ability to counter that pressure and keep you within your creative mindset is a real and valuable benefit.

8. Community

I’ve mentioned photowalks a few times already, and they are perhaps the most visible examples of how film photography can drive and build a community. 15-20 individuals, converging on a specific location at a specific time, to follow a pre-planned route while discussing film techniques and lending each other their cameras. Or even 39 events happening at once with over 800 photographers like our Big Film Photowalk! Heaven 🫶🏼

In fairness this one was less of a photowalk and more of a photodrink 😂

There are also virtual hangouts, Reddit groups, community exhibits, Instagram chats, darkroom sessions, Discord servers, photo competitions, local clubs, and much more. The trauma that film experienced when digital photography took over the world has had a lasting effect. The collapse of demand for film between 2000-2010 systematically destroyed supply chains, professions, retailers, and brands. Businesses had to adapt or go bust. A few ended up somewhere in the middle - and we are forever grateful to the quick thinking of key people that allowed Ilford, Kodak, Polaroid, Ferrania and many others to survive into the present day. None of them are in the same corporate form as they were at the turn of the millennium, but they are here and that’s what counts.

While this industrial scale turmoil was ripping out the old world, film photographers who weren’t enticed by the shiny promise of digital banded together to keep things ticking over. They saved local darkrooms, they invested in community funding, they continued to contribute to global film supplies - just enough to ensure that the analogue machine didn’t collapse entirely. We now feel like we’re coming out the other side of this disruption, but the bonds forged by that bunker mentality remain strong!

Newcomers to the hobby may not have any memories of the digital revolution, but they have still stepped seamlessly into the community structures that the turmoil created. I consistently hear that film beginners are pleasantly overwhelmed by the camaraderie they experience: the willingness of knowledgeable shooters to pass on their wisdom, to lend gear, to give friendly tips and critiques. The overall mood is about supporting each other and spreading the joy of film photography.

One of our ambassadors - Corinne Grey-West - runs Dark Art Sessions to teach techniques like Wet Plate Collodion portraits, emulsion lifts and plant-based photography

There is a practical point as well: film photography tends to be a passion rather than a profession for most practitioners. So there is no need for competitiveness over clients, marketing spend, or customers as there may be in other fields. And film photography is not immune to the wider problems of accessibility, discrimination and misogyny that remain prevalent in modern society. I know that there are many people who have had unpleasant experiences with companies and individuals. The analogue community isn’t perfect and I won’t pretend otherwise.

What I do consistently see is a willingness to identify, improve and fix those issues. Initiatives like SheHeartsFilm and LGBTQ+ photowalks are slowly building safe spaces to continue the work and further expand the community.

Conclusion: Why shoot film?

I hope you have enjoyed this exploration of the reasons that people choose to shoot film in a predominantly digital world. I would like to leave you with a couple of key points.

Firstly, everyone has different reasons to shoot film but the eight aspects I’ve described seem to capture most people’s experiences with analogue photography. However the balance of those aspects is highly individual. You are likely to find that one or two topics resonate strongly, and not care at all about the others. That’s totally fair and reasonable!

Secondly, I’m sure that the reasons to shoot film will continue to evolve as photography - and society - walks further into the AI-assisted future. There will be technological image-making breakthroughs in both hardware and software that are unimaginable as I write this in 2024. But I don't foresee any developments that will remove our need for a physical connection with our surroundings, for tangible experiences, for creative expression, or for our delight in anticipation. They are intrinsic to our human experience.

So for as long as possible in this uncertain world, I hope that there will be an active and passionate community advocating for the joy of film 🎞️

What do you think? Which topics resonate with you, and is there a perspective you think that I’ve missed?

Ready to dive in?

Keep Reading

View all

Eastman Kodak Releases KODACOLOR 100 & KODACOLOR 200 35mm Films: But What Are They?

Eastman Kodak has released two 35mm films: KODACOLOR 100 and KODACOLOR 200. But what do they look like, are they truly new emulsions, and what could this mean for the future of colour film now that Eastman Kodak has entered the still photography market alongside distributor Kodak Alaris?

Best Films for Autumn Film Photography: Top Tips for Capturing The Season

Autumn is a magical season for film photography, bringing rich colours, atmospheric weather, and unique tones and textures that we can bring to life with a range of film stocks. Whether you're capturing the natural colours of fall or prefer moody monochrome, we've got film recommendations and shooting tips to help you photograph the season beautifully.

Subscribe to our newsletter 💌

Sign up for our newsletter to stay up to date on film photography news, sales and events:

Free Tracked Shipping

On all UK orders over £50

Passion For Film

An unbeatable range and an on-site lab

Our Customers Trust Us

Thousands of independent 5* reviews

All Deliveries are Carbon Neutral

Independently audited and verified by Planet

- Opens in a new window.

45 Comments -

Peter ELGAR • -

Cliff Bown • -

Neale • -

Jeff • -

David Grewcock •

← 1 2 3 4 5 … 9 →

There are only 2 of us left in Brentwood & District Photographic Club using REAL FILLUM! Whenever one of us gets an award we shout out " Taken on FILM ! " The trouble IS that the Competition Judges who go around Clubs now cannot recognise ‘Film’ Photos and start talking about " This Car should be Cloned Out" when it was a darkroom Print on FP4+ in an Enlarger ! I get so annoyed – most Judges now say they have NEVER USED FILM ! I’m 87 now and started in 1951 when I was shown a Brownie Reflex Box Camera by my Mate who got a job in ILFORD LTD after his National Service — he got me to join the School Photographic Society and I saw ‘Contact Printing ’ on Kodak VELOX Chloride Paper using home-made print developers as shown by our Chemistry Master and I still make up my own Film and Print B&W Developers from Chemicals to this day — it is my Interest and has helped me beat my 6 Cancers messing about with ’Old Cameras and Real FILLUM’ !! KEEP SNAPPING you ALL !

My experience mirrors those above .Film exclusively since 1974, gradually shifting from colour to 95% b&w. Minolta X700s & 300s for the last 40 years, plus an Olympus mju or two & a much missed Ricoh 500G.Heroes: Henri C- B & Jane Bown [ no relation ! ] Great to see film gathering momentum

It’s about the process of the whole thing from top to bottom – from choosing film stock and shooting to development and printing.

Of course I love the look of the finished product, but it’s so much more than that. It is the experience of the entire process which simply cannot be replicated in a digital workflow. In short there isn’t a part of it that I don’t love – and that includes things like being limited to small number of shots per roll, or limited to a certain film speed or colour for the conditions. I shoot a medium format Bronica with interchangeable roll backs so I am able to mitigate this limitation somewhat, but I still enjoy the process of only having “two” options on any particular shoot. I take a budget 35mm with me to get pick up shots – and I’m usually happy with how these come out too.

The question could be – how many photographs do you need to take in order to get some keepers that you’re happy with? With film this will nearly always be less than digital (after a learning curve) – and I think that this is a much better approach overall. It feels more in tune with what you are trying to accomplish with a camera in the first place.

Obviously this only touches on a small part of the process as then you have the development and printing processes which yet again provide so much opportunity for control and experimentation. I’m not at all surprised at the resurgence of film – and I can see no reason why its popularity will not continue to grow and grow.

I started my photographic interest in 1971 when my girlfriends father gave me a Ross Ensign 6×4.5 I was an engineering apprentice and the knobs, springs, buttons etc fascinated me and still does.

I’ve just read your article and unless I missed it another reason to shoot film is your don’t need a computer. Although I use a computer in my photography I find the whole work involved time consuming and not really enjoyable. It takes you away from the actual process of taking pictures, learning how take better ones and not spending hours in photo editing software trying to make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear generally irritating.

I’m still, carefully, and very cautiously, returning to film.

I moved to digital after coming home with 13 rolls of film to develop… and even in my digital world I admit I’m very “enthusiastic” – one reason to not go back!

However a few years back I started to go to vintage events and the idea of taking images using old tech just appealed. I’m hoping my latest purchase, a vintage Kodak Pocket Vest Model B, will produce excellent results.

I wont return to film as such, but will enjoy being more “authentic” every now and again.